Newsletter: In Paris (Part 1)

From November 2021 to July 2022, I kept a newsletter, Dispatches & Ephemera, hosted through Revue. Now, I’m moving my posts here. Below, please find issues from November 2021 to February 2022.

November 7, 2021

Welcome to Dispatches and Ephemera, my (hopefully) weekly newsletter. My name is Keanu Heydari. I’m a doctoral candidate in History at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. This academic year, I’m in Paris conducting research towards my dissertation. I’m writing about Iranian emigrants in Paris in the 1950s up until the Iranian revolution of 1979. Going forward, in this newsletter you’ll find everything from personal updates to interesting archival discoveries. I hope you’ll join me on this journey!

Slightly off-center, in front of the Arc de Triomphe de l'Étoile

Benefits to having your phone stolen?

There I was, just getting off the phone with my mom at the metro stop directly across from my residence at the Fondation des États-Unis (FEU) at the Cité internationale universitaire de Paris (CiuP) in the 14th arrondissement of Paris. I was in a flurry—my dad had stayed with me for a little over a week and was heading back home to Los Angeles: he’d missed his flight because the results of his COVID test had expired. Mom was ringing non-stop while I was on the metro. As I got off the metro, I thought I’d put my phone back in my pocket. When I got back to my place, I discovered it was gone! More than a week after the fact, the “Find My iPhone” feature showed that my phone is now somewhere north of Sacré-Cœur, quite a ways away from the 14th.

Without a doubt, I can say that this has been one of the most productive weeks I’ve had in a while. Given that I’ve written about the disturbing effects of technology, particularly smartphones, on human subjectivity, the fact that I waste so much time on my devices is disconcerting (if not somewhat hypocritical).

In that essay, “Exteriorizing Subjectivity,” I wrote

[These] digital platforms are quickly evolving beyond what German social scientists have studied as Alltagsgegenstände, everyday objects that are ready-to-hand for human use. These platforms and the materiality of their own embodiment, particularly mobile phones, reterritorialize the domains of human subjectivity by mediating, facilitating, and accomplishing human communication through a commercially interested apparatus that harvests data and informatics unconsciously yet (supposedly) consensually supplied by the user. They realign the very texture of identity by virtue of normalizing individuals and cultivating a new erotic subjectivity and sensibility. Recall that Elsaesser noted the exteriorizing of interiority in the new society of control. Preciado, in a similar vein, observes the accelerated character of this process and the way it is facilitated by objects—agents of technological biocapital.

Sights around Paris

There’s something joyful and profoundly life-affirming about getting up every morning, walking leisurely to a café, and reading until I feel content. Sipping on an espresso or a café allongé and being immersed in the mental universe of a monograph or a novel is a privilege I’m not going to have when I return to Ann Arbor, so I’m enjoying it to the fullest while I have it here in Paris.

Tartines du petit déjeuner

Reading log

I’ve been reading Karl One Knausgaard’s new book, The Morning Star, and I’ve really been liking it. I’m about 260 pages in, so far. The book concerns the lives of a cast of characters in contemporary Norway. Each “chapter” is written from the vantage point of one of the characters, similar to how Kathryn Stockett’s The Helpwas written. I don’t know if this was intentional, but the text of the book (the English edition, I mean) runs 666 pages.

I’m still on the first chunk, titled “First Day.” The characters I’ve met so far with their own chapters are Arne (with his kids and unstable wife), Katherine (the priest in the Church of Norway whose marriage is facing difficulties—she’s my favorite character so far), Emil (a younger guy who works in a nursery), Iselin (a troubled girl who works at a local supermarket), Solveig (a doctor who is taking care of her mother, who seems to be suffering from Alzheimer’s disease), Jostein (somewhat of an asshole, a journalist who cheats on his wife), and his wife, Turid (an attendant at a psychiatric facility).

The text is characteristic of Knausgaard’s penchant towards naturalism and realist narrative description. I’ve felt that this has at times come across as a bit forced, especially when I encountered characters you could call moins élevé describing natural landscapes with poetic aplomb. Nevertheless, while this book isn’t a page turner like his 6-volume Proustian feat, My Struggle, was, I’m finding much to mull over and consider.

Knausgaard’s sections on the priest, Katherine, have been very thoughtful. The faithfulness with which he captures the intellectual ups and downs of a priest ministering in a Scandinavian country seems to indicate that he did a lot of research. Katherine was conducting a funeral service, and her eulogy was very compelling. She reads from Revelation 21:1-5, and then proceeds with this (pp. 198-199):

“The scripture I have just read, from the Revelation of St. John the Divine, is one of the most widely used of all in funeral services,” I said. “This is so because it gives hope, and concerns hope, a release from all that is painful in life, but especially that which is painful to us when someone close to us dies. There shall no longer be sorrow, for crying, for pain, and neither shall there be death—‘for the former things are passed away.’ It is easy to dismiss such words as the wishful thinking of a tormented individual, the wish for a new old in which all that is wrong with the present one will no longer exist. But if we think of what John’s revelation describes to us as being the kingdom of God, and if we think then of what God is, the words make sense. God is not sorrow and pain, God is joy. God is not death, God is life. And not least: God is eternal. And all of this is present now, in the place in which we stand today. Joy and life and eternity are with us. We are in the joy, as we share in life and share in eternity. But we are not joy, we are not life, we are not eternity. God is those things. We share, in a way, in God, as the minute perhaps shares in eternity, even though it is finite, and we do so even when we are crushed by sorrow, absence or pain. We are always a part of God. And what Jesus showed us is that God is a part of us. ‘Behold, the tabernacle of God is with men,’ the scripture says. It means that we are never alone. The fact that we sometimes feel ourselves to be alone is another matter. When we do, it is perhaps because we have shut God out, and shut ourselves in, with our sorrow and pain. Indeed, we can imagine such a life, locked in darkness while the light shines outside. What is the truth of that life? That it is dark in itself? Or that it has turned away from the light? If we open ourselves to God, through Jesus Christ, who is the light, we open ourselves to joy, life and eternity. All of which are present even in darkness, even in loneliness, even in pain.

“We are never alone.

“No, we are never alone.”

I’ll let you know what I think once I finish the book.

Elsewhere

Recently, I (@WoeToChorazin) was on my friend @henryjwallis‘s podcast, “Forms,” with @YAgamben. The podcast concerns Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben’s address to clergy in Paris, The Church and the Kingdom.

November 14, 2021

Château de Versailles

Routines and rhythms

It’s hard to believe that I’ve been in Paris since 20 October. With my dad back in Los Angeles (and back to caring for my cat, Thérèse—see below), figuring out how to manage well by myself has taken more time than I anticipated. My residence at the FEU at the CiuP, however, has been a welcoming home base as I learn to navigate the ins and outs of the city.

I only just received my replacement phone this Monday. However pitiful it may sound, I’ve been more or less stuck in the 14th arrondissement for over a week, not able to use a navigation application to find my way through the metro system. The Parisian metro differs significantly from London’s Tube. Figuring out which lines go where and at what time particular lines stop operating has been impossible without the assistance of technology.

After some turbulence getting my new phone set up with Orange (France’s equivalent to Verizon), everything has seemed to fall into place. I’m set up with a French bank account at BNP Paribas (only after, though, getting politely rejected by Crédit Agricole), I’ve enough coat hangers (cintres) to protect my articles of clothing, an electric kettle (bouilloire électrique) to make tea, and a set of wine glasses. Doing laundry at the FEU is remarkably easy, too.

I made a few friends at the FEU’s Halloween party—it’s lovely to see them around the building and walking about town. I anticipate making more acquaintances as I begin to feel more comfortable in my own skin and more accustomed to a casual register of French, something I never encountered in the classroom as an undergraduate.

Every morning, I head to a bistro on the rue Jourdan and read from a novel. I’m almost done with Karl Ove Knausgård’s new book, The Morning Star. I imagine I’ll have quite a bit to write about when I’m done with it. The next book I’m planning to read is 20th-century Iranian modernist Sadegh Hedayat’s The Blind Owl, which I’m reading in French translation (La chouette aveugle, translated from the Persian by Roger Lescot).

Third Worldist student activism

In Manijeh Nasrabadi and Afshin Matin-Asgari’s chapter, “The Iranian Student Movement and the Making of Global 1968,” in Chen Jian et al.‘s The Routledge Handbook of the Global Sixties: Between Protest and Nation-Building, the authors write the following in the conclusion.

“Obscured in the aftermath of the post-revolutionary consolidation of an Islamic Republic in Iran, and caught in the blind spots of Eurocentric historiography, the Iranian student movement’s contribution to secular internationalism needs to be written back into global narratives of the 1960s. More than filling an important gap in scholarship, it can help us reimagine new possibilities of present and future global protest movements that include the Middle East as a site of radical political knowledge production, resistance, and solidarity” (454).

Indeed, after reading Prof. Matin-Asgari’s book, Iranian Student Opposition to the Shah, and after meeting with him via Zoom on Thursday, I’m even more convicted of the fact that African and Asian Third Worldist student activism in the 50s and 60s is basically absent from mainstream accounts of the period.

Last week, I composed a Twitter thread about a particularly jarring monograph by Arthur Marwick.

Rather than force you to follow the thread, I’ll include my thoughts below.

I’m reading Arthur Marwick’s 700+ page comparative history (U.K., France, Italy, & U.S.) about the 1960s for my research prospectus and I’m a little taken aback at how much he hates “Marxism” and “postmodernism,” without understanding either very well. He coins the phrase “the Great Marxisant Fallacy,” which he defines as

“the belief that the society we inhabit is the bad bourgeois society, but that, fortunately, this society is in a state of crisis, so that the good society which lies just around the corner can be easily attained if only we work systematically to destroy the language, the values, the culture, the ideology of bourgeois society” (9).

I don’t know any serious leftists who believe this.

He also adds, “There was never any possibility of a revolution; there was never any possibility of a ‘counter-culture’ replacing ‘bourgeois’ culture” (9). Well… I’m not so sure about all that. I can tell you that the Confederation of Iranian Students, National Union (CISNU) directly contributed to the downfall of the Shah’s authoritarian regime.

Marwick also writes that “The theory of the dialectic…poses a sharp conflict between existing (bourgeois) culture and an oppositional culture … there is no more evidence for the existence of ‘the dialectic’ than there is for the existence of ‘the Holy Ghost’) (11). Shockingly, and seemingly weaseling his way out of analysis of Third Worldist student groups, Marwick writes ”To me the full significance of the sixties lies not in the activities of minorities but in what happened to the majority, and how it happened“ (13). How convenient.

He clarifies on the next page,

"That unspeakable oppressions and the struggles against them in the Third World received unprecedented attention from young people in the West is very much to the credit of these young people but does not mean that these events in themselves are the most significant features of the sixties” (14).

Oh boy…

We also get this gem:

“We need a history that tells it…as it was. We do not need a history which goes on and on about the wickedness of the bourgeoisie, or which is merely designed to support predetermined theories about language, ideology, narratives, and discourse, as agents of bourgeois hegemony” (18).

This book wasn’t written in 1970! It was written in 1998 and republished in 2012.

He writes: “I do not for one moment believe the post-structuralist claim that exists exist independently of author, artist, or director” (19). It’s an almost intentional misunderstanding of Foucault’s “disappearance of man” or Derrida’s “Il n'y a rien hors du texte.”

What’s interesting to me is that Marwick’s book is an otherwise very thoroughly researched text with a copious amount of documentation. The screed against discourse analysis, semiotics, and postmodernism was not at all necessary and signifies deep misreading and lack of charity.

Preparing for research

As I get closer to finishing my research prospectus, which should be completed by early December, I’ve started to think about my research activities in Europe and North America.

My research will take me around France, into Amsterdam, to Germany, and most likely back to California, as well. The primary sources I will consult include the fond of UEIF (Union des étudiants iraniens en France) documents; meeting minutes, pamphlets, and oral histories of the CISNU (Confederation of Iranian Students, National Union); Franco-Iranian diplomatic documents; contemporary literature about students, youth, and intellectuals during the 1950s-70s; urban planning documentation; and records of imprisoned, detained, and surveilled Iranians in Paris.

The archives I will consult include La Contemporaine in Nanterre, the Pierrefitte-sur-Seine site of the Archives Nationales, the Paris municipal archives (Archives de Paris), the François-Mitterrand site of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, the Paris police archives (Archives de la Préfecture de Police), the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam, and the Hamid Shawkat collection at the Hoover Institution Library in Stanford, CA.

November 24, 2021

Last week

November 20th was my 26th birthday. You’ll forgive the lapse in posting my Newsletter on the 21st—time got away from me when I realized Sunday had passed and I hadn’t written anything!

The night of the 20th was lovely: I got dinner with family at the Bouillon République (see photos below).

Archive Fever

On the 19th, I trekked to La contemporaine in Nanterre. On the 22nd and 23rd, I went to the Archives Nationales in Pierrefitte-sur-Seine. On the 24th, I visited the François-Mitterrand site of the Bibliothèque nationale de France. While I did consult hundreds of documents during these visits, the primary purpose was to familiarize myself with the layout of these sites and to obtain library/reading cards for each archive. There remain several archives that I will need to consult during the remainder of my stay in Paris, and in Europe, for that matter.

Learning about the UEIF (Union des étudiants iraniens en France), the Union of Iranian Students in France, has so far been an adventure. The task that remains includes building a narrative chronology of the various splinter organizations of Iranians in Paris and drawing conclusions about the broader importance of their activism for left-wing student movements in France during the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. I hope to find fonds of documents containing their meeting minutes, newspapers, propaganda, and tracts. Sources suggest that many of these will be found at the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam.

Prospectus progress

As of the 18th, I’ve finished a draft of my research prospectus. The research prospectus is a document that clearly lays out my intentions for researching in Paris, narrates my research questions, and provides an extensive literature review, a discussion about sources, a proposed chapter breakdown for the dissertation, and a research timeline. My advisor furnished me with an extensive commentary on this draft, and now it’s up to me to revise the document and meet with my dissertation committee in December to “defend” what I’ve written.

Workflows: Data management

A long time ago, I began a blog series called “Workflows.” Its mission, from the inaugural post, was the following:

My goal is to regularly document my research practices and workflow towards the end of envisioning an integrative system of knowledge production that doesn’t waste time and makes the most sense for people who have to deal with texts all day long. I’d also like to share my experiences with graduate school and academic life in your 20s and 30s.

The second piece in the series, “‘Welcome’ to Graduate School,” was aimed at introducing my readers to the problem of information management. At the blog’s conclusion, I wrote

In my next piece, I will focus on what life in your 20s and 30s means in academia. This piece will focus on what the problem of “Time Management” can mean in neoliberal institutions.

I never got around to writing this piece. I’m skeptical that I’ll ever get around to it, but I do want to resurrect the series by writing about my digital research infrastructure, how I use EndNote, Bookends, DevonThink, and Microsoft Word together, and what my research practices look like in plain language.

November 28, 2021

Thanksgiving in Paris

I celebrated Thanksgiving with my fellow residents at the FEU on the 25th. It was lovely getting to meet new friends and seeing folks that I’d already met at the Halloween party in October. The food was lovely: all the traditional fixings (turkey, authentic stuffing, mashed potatoes, green beans, etc.) and for €6 per person, it was a bargain.

My advisor at the University of Michigan warned me about the loneliness of research and reminded me of the importance of community building and friendship during the research year. Getting the chance to celebrate Thanksgiving with a diverse coterie of friends was a much needed respite from the isolation of archival research. I’ve also had the chance to make friends at my new church, the American Cathedral in Paris. It was thrilling to find an Episcopal home in Europe, and I’m looking forward to getting more connected with this parish.

I also have to mention that keeping in touch with my friends at Michigan (especially Paige, Zoe, Lucas, Irene, and Frank, among many others) has been thoroughly life-affirming, if not essential. Learning about their research, and benefiting from their intelligence and camaraderie, has kept me going through my transition from Ann Arbor, to Los Angeles, and now to Paris.

Thanksgiving at the FEU

I will submit a final draft of my research prospectus on December 2. My prospectus defense (!) is scheduled for Thursday, December 9 at 11:30 AM (EST)/5:30 PM (CET). Unfortunately, this meeting is closed to the public, but I’m more than happy to keep you in the loop if you’re interested—simply contact me (below).

Below, find an image of a UEIF propaganda magazine that I discovered at the BnF, Iran en Lutte.

"Iran en Lutte," no. 2, Nov. & Dec. 1978. Source: BnF.

Reading reflections

I’ve spent the past week or so reading about intellectuals in Iranian history, from the late nineteenth century to the present. My focus has largely been on Farzin Vahdat’s God and Juggernaut: Iran’s Intellectual Encounter with Modernity and Afshin Matin-Asgari’s Both Eastern And Western: An Intellectual History Of Iranian Modernity. Prof. Matin-Asgari has graciously agreed to be on my dissertation committee, and I look forward to working with him.

Vahdat’s text introduced me to figures like Malkum Khan, Kermani, Akundzadeh, Talebuf, Afghani, Sepahsalar, Sheikh Fazzolah Nuri, Mirza M.H. Naini, Hussein Kazemzadeh (Iranshahr), Seyyed Ahmad Kasravi, Mohammad Amin Rasulzadeh, and Taqi Arani, among many others.

Vahdat writes

… I will evaluate the key intellectual elements of the Iranian encounter with modernity over the past century and a half. Iran’s early intellectual encounter with modernity in mid-nineteenth century, like that of many other Third World countries, began as a response to the imperialist onslaught waged primarily by tsarist Russia and Britain. In their attempts to counter the onslaught, the intellectuals and reformers appropriated two aspects of modernity available to them: the “positivist” aspect, emphasizing such categories as technology and efficient bureaucracy found in Western modernity; and the cultural aspect of modernity, focusing on the more democratic facets of modern civilization. This dualist approach to modernity has characterized much of Iran’s experience with modernity even though the democratic aspect has been eclipsed by the positivist for most of this relatively short history. Nonetheless, the democratic aspect of modernity in Iran, reflected in attempts to build modern institutions, specifically those of the Constitutional Revolution of 1906, has never been eradicated from Iran’s cultural soil (xvi).

December 7, 2021

Five issues and a year in review

I’m not sure what it says about my work ethic, but I did not anticipate publishing five issues of my newsletter at this pace! Your encouragement and engagement with my brief reflections have motivated and inspired me to press on despite not always being inclined to share my thoughts and activities.

The music streaming application Spotify has a feature called “Wrapped” that shows (in addition to how our data is basically up for grabs) what our most listened-to tracks and artists of the year were.

You can follow through the Tweet above to see what Spotify included for my “Wrapped” data. The groups and musicians listed above (Joy Division, Sandra McCracken, TV Girl, Lana Del Rey, and ABBA) have been my constant companions through the travails of graduate student life, from finishing up my preliminary exams to submitting my research prospectus last Thursday.

Sandra McCracken’s 2020 album, Patient Kingdom, has been a friend to me. Her track, “I Am One,” was my anthem as I struggled through impending deadlines and fibromyalgia pain:

Gracious light illuminate / Every shadow of this offering / Draw the gold / From the hidden place / I am one with You in glory

Gracious fire purify / In the flames of Your redemption / Burn away every stain / What remains is love unending

The imagery of refining fire has been a potent metaphor for both my academic and spiritual lives. Before we can grow, our imperfections need to be brought to the surface—this is a painful process. Like a truthful mirror, the refining fire must show us the cracks and bumps littering our image, shattering the imaginary picture of our Ego that we hold so dear.

The intensity of research and production at the graduate level leaves little room for fantasies about our abilities. I’m very grateful that my advisors, in a spirit of love, care to point out the places where I need to grow. I’m of the opinion that the very awareness of our imperfections helps us grow through, in, and out of them.

In going through some of my past writing, I came across a two-part series I wrote while I was an undergraduate. I posted the reflections on my blog this year and hope you’ll take a look at them. The first is called “Suffering and the Promise,” and the second “Healing and the Promise.” The pieces deal with being diagnosed with fibromyalgia, dealing with chronic pain, and finding hope where there seems to be none.

2021: Qu'est-ce qu'une année ?

My Parisian journal

If you’ve been following my blog, you’ll know that one habit I take (somewhat) seriously is keeping a diary. If not every day, then at the very least once a week. As the year goes along, I periodically transcribe my handwritten diary entires into a software called Day One. For this issue of my Newsletter, I read through some of my entries and would like to share some key takeaways.

At the start of the year, I continued to heal from a herniated disk I got during the summer of 2020. Today, I feel much better and don’t feel any pain in my lower back. From going to physical therapy three times a week to feeling completely healed, this was indeed a profound event of my year.

In June, I decided to make the transition away from the Catholic Church into the Episcopal Church (TEC). I hope to write a blog post about this by the time I get received into TEC.

In August, I finished my preliminary exams and advanced to candidacy.

One of my closest friends, Mitch, got married in October. I gave a speech at his wedding and couldn’t be happier for him and for his new family!

You’ve been kept abreast of what I’ve been up to since November 7th.

On this Thursday, December 9, I will have my research prospectus defense meeting with some of my advisors! Please keep me in your thoughts and prayers as I prepare for this occasion.

My reading cart

Take a look at some books on my to-read list.

December 13, 2021

Research updates

On Thursday, December 9, I successfully defended my research prospectus! My advisors read through the prospectus and highlighted areas of strength and areas of potential improvement. Now, I’ll be beginning my journey of research towards my dissertation in earnest. I will work towards revising my current chapter outline to incorporate more archival evidence and new theoretical approaches gleaned from relevant secondary sources.

Newsletter hiatus

I’m so grateful for all of you! Thank you for taking time to read my newsletter. I plan on taking a break from writing regularly until January 9 for the holiday season. Stay in touch with me through Twitter.

In Memoriam: Tyler Stovall

Tyler Stovall, one of my favorite French historians, has passed away. I would like to recommend his newest book, White Freedom, mentioned below.

Interesting reads

Links

January 9, 2022

Research updates

My last issue announced a hiatus of my newsletter until today, January 9th, 2022, for the holiday season. I spent Christmas and New Year’s Day with family and friends in Paris. I got much needed rest and relaxation and enjoyed lovely food and wine.

While I didn’t get much archival research done, I did catch up on a few secondary sources, namely Gérard Noiriel’s Le creuset français : Histoire de l'immigration (XIXe-XXe siècle), Safoura Tork Ladani’s L'Histoire des relations entre l'Iran et la France : Du Moyen Âge à nos jours, Ali Misepassi’s The Discovery of Iran: Taghi Arani, A Radical Cosmopolitan, Mahmoud Delfani’s edited volume L'Iran et la France malgré les apparences, and Mahmoud Delfani’s book series Traversée occidentale.

Views of Paris

Musée d'Orsay: "Signac, the Collector"

The exhibition at the Musée d'Orsay, “Signac, the Collector,” was breathtaking. Signac’s use of color is remarkable. A member of the neo-Impressionist and Pointillism schools, Signac, along with Georges Seurat, opened new paths for artistic expression in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Over the past fifteen years or so, collecting has been the subject of renewed interest, and has given rise to numerous studies, exhibitions and publications. The Signac collection is a real textbook case of this, as it reflects the viewpoint and biases of an artist who was particularly active in the art scene of his time. The Museum’’s collaboration with the Archives Signac, which, in addition to the artist'’s correspondence, keeps the notebooks in which he recorded his purchases, makes it possible to establish a precise census of the paintings, drawings and prints that belonged to him.

"The King's Animals" exhibit at The Palace of Versailles

"The King's Animals" exhibit at The Palace of Versailles

The King’s Animals exhibition at Versailles was a whirlwind, too.

The exhibition aims to illustrate the bond between the Court of Versailles and animals, whether “companion animals” (dogs, cats and birds, mainly), exotic beasts or “wild” creatures. No study of the Palace during the reign of Louis XIVwould be complete without considering the Royal Menagerie, which the Sun King had installed close to the Grand Canal. It was home to the rarest and most exotic animals – from coatis to quaggas, cassowaries to black-crowned cranes (nicknamed the “royal bird”) – constituting an extraordinary collection in which the king took ever greater pride.

Interesting reads

Links

Discrimination against Iranians

On 18 January 2022, I attended a virtual conference via Zoom (now available on YouTube) hosted by the National Iranian American Council (NIAC) on the topic, “Othering Iran: How Dehumanization of Iranians Undermines Rights at Home.” The panel was based on the report of the same name by Assal Rad. The conference included Rad herself (Senior Research Fellow, NIAC); Neda Maghbouleh (Canada Research Chair in Migration, Race, and Identity at the University of Toronto); Niaz Kasravi (Founder & Director of the Avalan Institute); John Ghazvinian (Executive Director of the Middle East Center at the University of Pennsylvania); and Yara Elmjouie (Video producer, journalist, and host at Al Jazeera’s AJ+). Ghazvinian recently released his informative survey, America and Iran: A History, 1720 to the Present (Knopf, 2021).

In the report, Rad writes that

The systematic demonization of Iran, and by extension Iranian people and those of Iranian heritage, is so prevalent in U.S. political discourse that it permeates American society and popular culture as well. This process has not only led to the dehumanization of an entire group of people, but it also informs U.S. policy positions on Iran.

The real-life consequences of these policies are evident in the discriminatory closures of Iranian-American bank accounts, the freezing of transactional accounts simply for using words like “Iran” or “Persian,” immigration policies that prevent family members from Iran to visit their Iranian-American family, discriminatory questions when entering the United States as a U.S. person, and an overall sense of hostility that has been experienced in numerous ways. Additionally, the collective punishment of sanctions and fear of possible war with Iran impacts Iranian Americans by hurting their families who still reside in Iran.

The conference covered the different stages of discriminatory depictions of Iranians in Western media—highlighting shocking rhetoric used by American politicians to stigmatize Iranians in general (and by implication, Iranians residing in the United States). Another highlight was the unafraid emphasis on white supremacy as an analytic that needs to be dismantled both within and without the Iranian community. Political divisions in the Iranian diaspora notwithstanding, solidarity with BIPOC in the struggle against white supremacy, neoliberalism, and cisheteropatriarchy is essential in rejecting categories of Aryan-ness and whiteness, on the one hand, and otherness and alienation, that have been foisted on the Iranian diaspora since the nineteenth century by the structures of white supremacy.

The conference led me to discover several articles that will inform my own research agenda: namely, Evelyn Alsultany’s “Representations of Arabs, Muslims, and Iranians in an Era of Complex Characters and Storylines,” and Sam Fayyaz and Roozbeh Shirazi’s “Good Iranian, Bad Iranian: Representations of Iran and Iranians in "Time” and “Newsweek” (1998–2009).“ I’ve now also added Maghbouleh’s book, The Limits of Whiteness: Iranian Americans and the Everyday Politics of Race, to my reading list.

Research updates

My last issue included a list of books that I’m currently reading. The texts will help to shape a better-defined research agenda than I currently have. This past week, I’ve been diving into the archival materials I’ve already collected and have begun the process of sorting, reading, annotating, and analyzing. While I’m still visiting archives in and around Paris, my next big research trip will involve a visit to Amsterdam to consult the International Institute of Social History. Current COVID-19 restrictions prevent a visit before March, but I’m making the most out of my time in Paris.

The next big decision I have, as it pertains to my research, will be about the scope of my research—do I want to limit my studies to radical student activism in France in the 1950s-1960s, or do I want to broaden the scope of my study to ask questions about Iranian identity, Muslim identity, secularity, and the complicated histories of assimilation in France?

Theological reflections

A new feature I’d like to add to my newsletters beginning next week is a set of theological reflections based on the Episcopal Church’s adaptation of the Revised Common Lectionary. Having been inspired by the daily-devotional featuring selections by Bonhoeffer’s works (I Want to Live These Days with You) and Fleming Rutledge’s new sermon-devotional collection (edited by Laura Bardolph Hubers), Means of Grace: A Year of Weekly Devotions, I want to share my thoughts about Sunday readings as often as I can.

See below some new books that are on my personal docket.

February 2, 2022

Research Updates

La bibliothèque de documentation internationale contemporaine in Nanterre

Since I last wrote on 01/19, I’ve done research at the BnF, La Contemporaine in Nanterre, and the Archives Nationales in Pierrefitte-sur-Seine. I’ve found a few fonds of documents that will prove interesting for more broadly conceptualizing the spaces Iranians inhabited in Paris in the twentieth century. Paired with my secondary readings on French immigration, the relationship between the French state and Islam, and the history of the colonial doctrine of assimilation, this research will help to configure Iranian immigrants in the French cultural imaginary as it pertains to questions of race, migration status, and political orientation between Tehran and Paris.

I’ve been reading Naomi Davidson’s 2012 book, Only Muslim: Embodying Islam in Twentieth-Century France, and I find the author’s argument striking. That Pierre-André Taguieff’s trajectory of the biologization of contemporary racism towards its culturalization is not applicable in the case of “French Islam,“ but precisely the reverse situation is a bold claim. Davidson argues that a rigid, orientalized, and aestheticized Moroccan form of Islam came to be imposed on the majority Algerian immigrant population in France. If Davidson’s argument holds, which I believe it does, then my job becomes somewhat easier. I will now have to figure out the ways in which Iranian Muslims belonged (or not) to the coterie of West African and other immigrants who were generally excluded from the cadre of “French Islam” as it was imposed on Algerians. How best to articulate the differences between "secular” Iranians in Paris and those with deeper religious commitments?

Theological reflections

In the place of a reflection on the lectionary readings for this Sunday (2/6), I will gloss some citations and thoughts from my reading of Gerald McKenny’s The Analogy of Grace: Karl Barth’s Moral Theology (Oxford, 2010).

Barth’s theological ethics begins “with the bold and rather startling claims that God alone knows and judges good and evil and that God accomplishes the good in our place” (ix). Barth’s framing of “the command of God” means “God’s judgement summons us to participate in the divine knowledge of good and evil as those who hear this judgement (which is always spoken through a fellow human being) and confirm it with our free decision” (ix).

For Barth, election involves a twofold determination (Bestimmung) of divine grace; it includes both God’s gracious and free self-determination to be with and for humanity and God’s determination of humanity to exist as the one whom God is with and for, that is, to be the recipient of God’s grace and the witness to it. In this latter determination, humanity is chosen to glorify God, and in the freedom given by God for this service and commission humanity, too, is glorified. However, this determination is not, as it were, hardwired into humanity as God’s elect. It is, rather, a determination of the elect as person and thus as free subject. It therefore confronts human beings with the question of their own self-determination in light of their determination by God (3-4).

Our “existence as acting subjects should signify in a distinctively human way God’s gracious self-determination to be with us and for us in all God’s deity, that human life should be lived as an analogy of grace” (5). It is precisely in Jesus Christ “who obeys the command of God by being the elect one in all that he is and does that the good is actualized. As such, the reconciliation accomplished in Christ is not only the restoration of the covenant in the far of its sinful rejection by God’s human partner; it is also the actualization of the covenant in its fullness” (6). Finally, moral theology for Barth “has to do not with a good which human beings find in themselves but with the relation of human beings to a good that has already been accomplished in Jesus Christ” (7). “The command of God is not a demand that we fill something that is lacking but rather that we confirm what has already been done” (7).

Practically speaking, the command of God is an ethical event [ethische Ereignis], which is “‘the encounter [Begegnung] of the concrete God with the concrete man,’ or more specifically, between ‘a highly particular, concrete, and special command ’ and ‘a concrete and specific human choice and decision’” (7). This ethical event is an analogy of grace in that humans mimetically refract the glories of Christ in as much as we are hidden in him.

Set your minds on things that are above, not on things that are on earth, for you have died, and your life is hidden with Christ in God. When Christ who is your life is revealed, then you also will be revealed with him in glory (Col. 3:2-4, NRSV).

The mystery of this ethical event as it pertains to our divine hiddenness in Christ is something about which I’ve been reflecting. Barth sees the ethical imperative not as a task we must complete but as a the dynamic wherein we respond in gratitude and responsibility to God having already taken responsibility for us in the Christ-event. God having for us already accomplished our reconciliation and our sanctification means grace goes all the way down. The concrete situation of the ethical event involves understanding the thrown-ness of human beings into a particular lifeworld, of course. And yet, we are still responsible before God to be the ones for whom God has elected as partners in the covenant. “To be grateful is to know oneself as the recipient of the gift rather than to assert one’s parity with the giver by packing it back, just as responsibility is properly exercised in response to God’s responsibility for us rather than as the assertion of our likeness to God” (19).

By establishing and fulfilling the good in our place, grace interrupts all of our striving for the good and calls it into question. Yet precisely as such, grace summons us and, by the Holy Spirit, empowers and directs us to exist in a human analogy to grace, and thereby to glorify the God who glorifies us (21).

Interesting reads

Links

February 17, 2022

Research updates

Centre des Archives diplomatiques at La Courneuve

Since I last wrote (02/02), I’ve spent time at a new archive at La Courneuve: the Centre des Archives diplomatiques du ministère des Affaires étrangères. Because my access to archives in the Netherlands and Germany is still limited, I decided to try my luck at French diplomatic and foreign affairs archives.

What I discovered almost immediately is that the documents I encountered revealed the mechanics of French diplomatic bureaucracy. They don’t necessarily speak to social historical concerns, but they do shed light on questions that the French state understood to be important. I encountered dossiers discussing Iranian reactions to the Algerian War, concerns about the political radicalization of Iranian students in Paris, and the management of official visits of the Shah to Paris and French officials to Tehran.

These dossiers are filled with telegrams, communiqués, and reports about official diplomatic relations between France and Iran, but occasionally some fonds will include sections about “Iranians in France,” or “French in Iran.”

In the document above (February 1962) begins,

In early May 1961, Iranian schoolteachers, followed by all teachers and almost all students, organized a series of demonstrations in Tehran that led to the resignation of the government of Mr. Cerif Emani and its replacement by a team of technicians headed by Dr. Ali Amini, one of the few liberal aristocrats in the country.

The first page concludes with this observation,

In any case, all these events are not without influence on the Iranian colony in Paris and especially its students.

I’m looking forward to going through the documents I’ve collected and sharing more with you as I learn more.

Theological reflections

The Gospel reading for the Seventh Sunday after the Epiphany (02/20/2022) is Luke 6:27-38 (NRSV).

“But I say to you that listen, Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who abuse you. If anyone strikes you on the cheek, offer the other also; and from anyone who takes away your coat do not withhold even your shirt. Give to everyone who begs from you; and if anyone takes away your goods, do not ask for them again. Do to others as you would have them do to you. If you love those who love you, what credit is that to you? For even sinners love those who love them. If you do good to those who do good to you, what credit is that to you? For even sinners do the same. If you lend to those from whom you hope to receive, what credit is that to you? Even sinners lend to sinners, to receive as much again. But love your enemies, do good, and lend, expecting nothing in return. Your reward will be great, and you will be children of the Most High; for he is kind to the ungrateful and the wicked. Be merciful, just as your Father is merciful. Do not judge, and you will not be judged; do not condemn, and you will not be condemned. Forgive, and you will be forgiven; give, and it will be given to you. A good measure, pressed down, shaken together, running over, will be put into your lap; for the measure you give will be the measure you get back.”

David L. Ostendorf [“Theological Perspective on Luke 6:17–26,” in Feasting on the Word: Preaching the Revised Common Lectionary: Year C, ed. David L. Bartlett and Barbara Brown Taylor, vol. 1 (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2009), 358] offers some helpful insight on this passage:

In Luke, God breaks down the doors, splinters them, and in Jesus boldly proclaims to the disciples, the crowds, the church the coming of a dramatically different realm. Here Jesus stands “on a level place” with the disciples and the multitude, not on a mount above them. He declares to those who have left everything to follow him that theirs is the kingdom of God, regardless of how reviled and defamed they might be. And he warns those who do not follow in this way that their lives will be woeful. God is turning the world upside down, and taking discipleship far beyond a simple “follow me” to a level of sacrifice that is nothing less than daunting.

In this world, however, even poverty does not translate into blessing. New Testament scholar John Dominic Crossan distinguishes between the pauper/peasant and the destitute/beggar. He asserts that “Jesus declared blessed, then, not the poor but the destitute, not poverty but beggary.”1 God’s blessings do not fall on “the poor” simply because they are poor. The utterly reviled and expendable of the human family, the wretched of the earth, are the favored of God’s blessings.

In the edited volume, Thy Word Is Truth: Barth on Scripture (ed. Hunsinger), A. Katherine Grieb notes that

Barth insists that the entire Bible is full of ethics, but we will fail to see the woods for the trees if we are looking for “universal rules,” which are not to be found there (II/2, 672). We must divest ourselves of the fixed idea (fixed since Kant) that only a universally valid rule can be a command (II/2, 673) because God’s commands belong directly to a specific history and must be left in all their historical particularity and uniqueness (II/2, 673) (99).

Furthermore,

Barth insists that the Sermon on the Mount, like any other biblical text, must be read in the light of its context, that is, in a special connection with the theme of God’s reign as it has come in the person of Jesus Christ in fulfillment of Old Testament prophecy. This is as true of the Sermon on the Mount as it is of the other great discourses in Matthew. Now it is Jesus himself who defines the sphere in which he is present with those whom he calls. The order that constitutes the life of the people of God, for that is what the Sermon on the Mount is, as it repeats and confirms the Ten Commandments and the rest of the Law, is now fulfilled by God in Christ for human salvation (II/2, 687). So even if the Sermon seems to be concerned with problems of human life (marriage, swearing, enemies, almsgiving, praying, and fasting), this is incidental and by way of illustration—which is why it has always proved impossible to construct a picture of the Christian life from these directions. The picture they offer is the picture of the One who gives these directions and of the one who receives them. The picture shows God’s reign, Jesus Christ, and the new human creature. They point, as the Ten Commandments point, to what God has done and is doing in Jesus Christ (II/2, 688).

So Barth can say: “If the Ten Commandments state where [humanity] may and should stand before and with God, the Sermon on the Mount declares that [it] really has been placed there by God’s own deed. If the Ten Commandments are a preface, the Sermon on the Mount is in a sense a postscript” (II/2, 688). The only question now is whether the church will live or not live in the fullness of life already granted to it. The Sermon on the Mount declares: “God has irrevocably and indissolubly set up the kingdom of [God’s] grace … which as such is superior to all other powers, to which, in spite of their resistance, they belong, and which they cannot help but serve” (688) (102).

The radical revolution of the Christ-event turns the world upside down. Rather than prescribing a to-do list, Luke’s Sermon on the Mount is the heralding of God’s kingdom, it is the vocalization of the command of God in his justice and righteousness that is vindicated in the resurrection of the Son of God.

Interesting reads

Links

February 25, 2022 (#11)

Research updates

Last I wrote, I’d done research at the diplomatic archives in La Courneuve. Over the weekend (2/18-2/21), I visited my friend and colleague Paige Newhouse in Berlin. Paige researches Vietnamese migration to Germany in the late twentieth century.

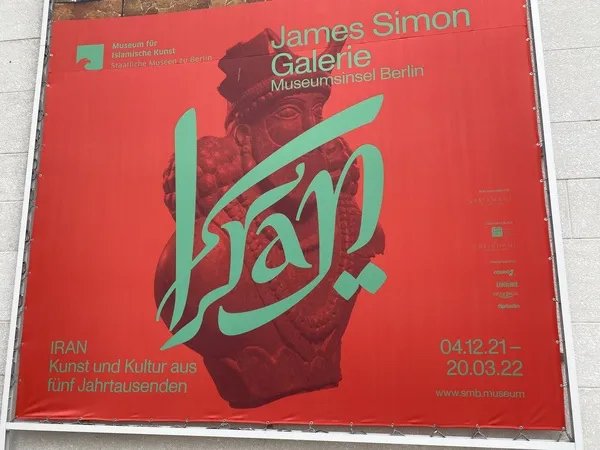

Apart from spending time with friends in Berlin, the highlight of my trip was visiting the exhibition on Iranian art and culture at the James-Simon-Galerie.

While the art, ceramics, and historical presentation were breathtaking, I did find the lack of self-conscious reflection on the history of German Orientalism disconcerting. Nowhere in the exhibit do we see extended reflection on acquisitions or the complicated history of German-Iranian relations. The lack of coverage of nineteenth- and twentieth-century art and poetry was disappointing, as well.

In March, I’ll be traveling to Tübingen and Amsterdam for more archival research.

Theological reflections

The Gospel reading for the Last Sunday after the Epiphany (02/27/2022) is Luke 9:28-36 (NRSV).

Now about eight days after these sayings Jesus took with him Peter and John and James, and went up on the mountain to pray. And while he was praying, the appearance of his face changed, and his clothes became dazzling white. Suddenly they saw two men, Moses and Elijah, talking to him. They appeared in glory and were speaking of his departure, which he was about to accomplish at Jerusalem. Now Peter and his companions were weighed down with sleep; but since they had stayed awake, they saw his glory and the two men who stood with him. Just as they were leaving him, Peter said to Jesus, “Master, it is good for us to be here; let us make three dwellings, one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah”—not knowing what he said. While he was saying this, a cloud came and overshadowed them; and they were terrified as they entered the cloud. Then from the cloud came a voice that said, “This is my Son, my Chosen; listen to him!” When the voice had spoken, Jesus was found alone. And they kept silent and in those days told no one any of the things they had seen.

Sonderegger (ST, I) writes, “So we must say that, like the Transfiguration itself, these heavenly visions are—to borrow the powerful phrase of Karl Barth’s—the Reality of the Other side in the language and terms of the near side” (438). And, “For Barth, Jesus Christ just is the Other Side manifest and living and sovereign on this side, the side of time and tide, of suffering and death and hope for deliverance” (439). Calvin (Institutes, 4.17) writes, “[The purpose of the Transfiguration] was to give them for the time a taste of immortality. Still they cannot find there a twofold body, but only the one which he had assumed, arrayed in new glory.”

Anastasius, Monk and Presbytery of Sinai, wrote

For what is greater or more awe-inspiring than this: to see God in human form, his face shining like the sun and even more brightly than the sun, flashing with light, ceaselessly sending forth rays, radiating splendor? To see him raising his immaculate finger in the direction of his own face, pointing with it, and saying to those with him there: “So shall the just shine in the resurrection; so shall they be glorified, changed to reveal this form of mine, transfigured to this level of glory, stamped with this form, made like to this image, to this impress, to this light, to this blessedness, and becoming enthroned with me, the Son of God.” And when the angels then on the mountain heard what Christ had said, they trembled; the prophets were struck with wonder; the disciples fell faint; creation rejoiced when it heard of its transformation from corruption to incorruptibility; the mountain was filled with delight, the fields were joyful, the villages sang songs of praise; the nations came together, the peoples were exalted; the seas chanted hymns, the rivers clapped their hands; Nazareth cried out, Babylon sang a hymn, Naphthali celebrated a festival; the hills leapt, the deserts bloomed, the roads helped travelers along; all things were unified, all things were filled with joy.

Interesting reads

Links